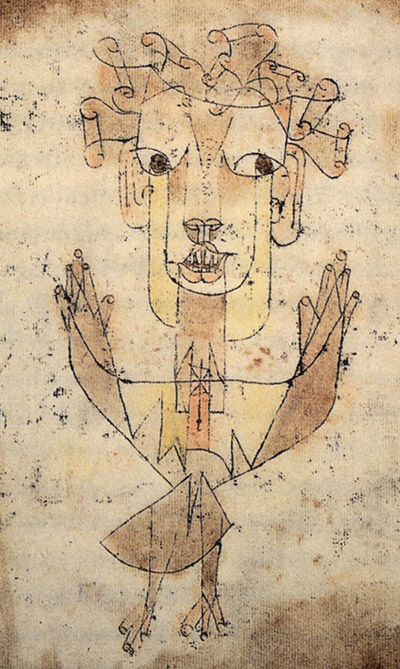

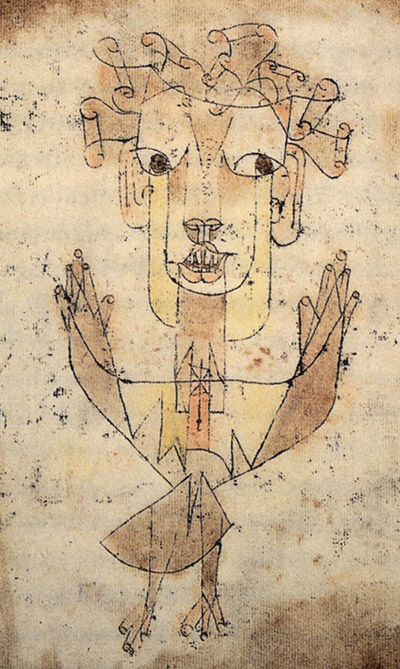

“A Klee painting named Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history.”

Walter Benjamin, Ninth Thesis on the Philosophy of History

In his Ninth Thesis on the Philosophy of History, Walter Benjamin offers up an abrupt and searing dismissal of the idea of progress in history, central to our modern consciousness, and particularly so after the Enlightenment. He offers his devastating little parable because of the breathtaking experience of barbarism in our times. Benjamin’s narrative description of Paul Klee’s painting Angelus Novus (which he owned at the time) comes after his famous remark in the Eighth Thesis, “There is no document of civilization that is not at the same time a document of barbarism.”

In full, Benjamin writes, “A Klee painting named Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.”

In full, Benjamin writes, “A Klee painting named Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.”

We do not yet find ourselves facing the stark realities that led Benjamin, just a short time after writing this, to take his own life in 1940. But we maintain that the shock of barbarism we feel today is a similar one.

We thought we were (albeit highly imperfectly at both home and abroad) a country of democratic ideals, a country that believed in the dignity of the entire human race, a country that believed that we could find our way to greater dispensations of universal human freedom. Instead we find ourselves asking, along with Benjamin, Schiller’s question from On the Aesthetic Education of Man–given that there is progress in history, such that the future is something we can craft and bring about using our reason, then “Why is it that we still remain barbarians?”

Benjamin’s answer is rooted in Jewish Messianism. In this area of In Dark Times, we ask after the sources of our apparent barbarism, and what the persistence of barbarism in our times means, for our hopes for the future, given that we still regard ourselves as distinctly modern persons.

In full, Benjamin writes, “A Klee painting named Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.”

In full, Benjamin writes, “A Klee painting named Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.”